AI has been generating a lot of discussion lately, not just Artificial Intelligence (an oxymoron?) but also Artificial Insemination for breeding herds. We’ve had a number of clients implement an Artificial Insemination program with their heifers so, to get an understanding of the economics of the option, we analysed their data from the exercise.

The costs are far easier to quantify than the benefits associated with undertaking an AI program. The total cost will include the price of anything additional and necessary for the AI program to take place. This includes, semen straws, semen transportation and storage, preg-test pre-AI, syncing of heifers, AI technician, and additional labour (e.g. additional musters, extra time in yards).

Theoretically, AI enables rapid dissemination of superior genetics, allowing producers to make faster progress in their breeding programs compared to natural mating. The ability to use semen from elite sires accelerates the improvement of desirable traits in the herd, promoting traits such as increased growth rates, improved carcass quality, and enhanced fertility. Those undertaking AI with heifers have also identified the following potential benefits;

- achieving a tighter and earlier calving pattern leading to better re-conception rates, heavier weaners and easier supervision

- a reduction in the required number of bulls, and,

- reduced dystocia through targeting low birth weight bulls

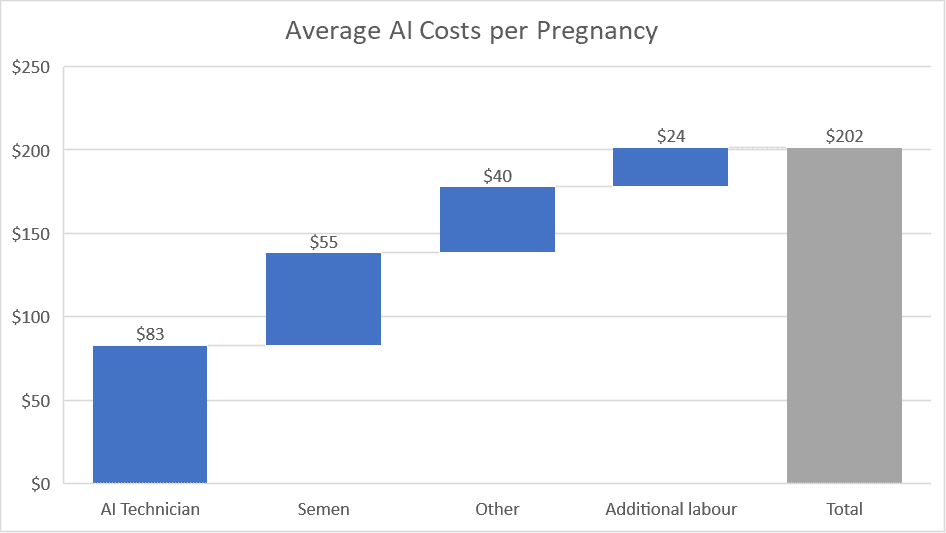

Let’s start with the costs. We’ve pooled the data together from the five clients in southern Queensland who undertook AI programs. In total they inseminated 1,400 heifers with total incremental costs of $149,600 or $107 per heifer inseminated. The success rate across the five averaged 53% conception rate, resulting in 742 pregnancies, with an incremental cost of $202 per pregnancy. The range in conceptions was 46%-66% and the range in incremental costs per pregnancy was $146 to $295. The below graph shows the composition of the cost per pregnancy. Keep in mind that this cost doesn’t account for losses from preg-testing to weaning. If we assume 5% losses, then this increases the cost to $212 per weaner, meaning we need to realise a benefit of $212 or more for the exercise to break even; or let’s say at least one and a half times that to provide an economic return that justifies the risk.

Let’s start with the bulls. The need for less bulls is cited as a benefit, however the heifers that don’t conceive through AI, will be cycling simultaneously on their subsequent cycle so will still require significant bull power in the mop up bulls. If we assume that;

- the bull joining percentage can be reduced by 1%,

- our bulls cost $10,000,

- last for 5 years, and

- are worth $2,000 at the end of their life,

then this saving reduces the net cost of the program to $183 per weaner (range $117 to $295).

The other benefit from bulls is through sourcing better genetics for an AI program than can otherwise be sourced for paddock bulls. This may be the case in some breeds, however there are many examples of good quality, high indexing bulls able to be purchased for similar money to average or undescribed bulls. Indexes are effectively the weighted average genetic merit of animals for different markets and reflect the expected relative profit per animal from both sale of progeny and daughters flowing through the herd. This makes it a useful and simple measure to look at the difference in profitability between bulls.

If we make the (very questionable) assumption that AI allows access to bulls that index at the top 10% of your breed, whereas you’d only be able to access average indexing bulls otherwise. The difference between the top 10% and average for maternal indices of prominent breeds varies, but is up around $40 in some. Given the bull is only half of the genetic equation, half of this benefit will flow through to the calves, so a bull which indexes $40 higher should result in $20 more profitability in their progeny. This still leaves us over $160 short, on average.

Dystocia is a very big cost, so there is significant benefit is reducing dystocia, however for this benefit to come from AI then it must be assumed that low birth weight bulls cannot be purchased as paddock bulls, also heifer specific issues such as pelvic size are simultaneously addressed.

The benefit from tighter and earlier calving requires further analysis. If the heifers are all at or above their critical mating weight and bulls are sound and functioning, then conceptions in natural mating should be 60% per cycle. This is higher than most of the five properties achieved through AI.

The benefit from heavier weaners is also therefore questionable.

Undertaking the AI program for the purpose of breeding your own bulls would change the benefits. Another scenario maybe, if there is sufficient herd fertility, to not use a mop up bull and only retain those heifers that conceive through AI, the cost per weaner would still average over $130 in this example.

AI may be an economical choice for some producers, however for commercial breeding businesses we’re not sure that the benefits exceed the costs in what is an expensive exercise.

Sourcing quality genetics that will take your herd forward is important, however you do this. This is why we developed Top Studs, as a way of identifying who the breed leaders are for genetic merit and displaying their genetic profile. Understanding the bull cost per calf is very important when assessing your genetic investment, we’ve developed an online tool which calculates the bull cost per calf and shows what proportion of genetic change in your herd is driven by bulls.