By Ian McLean

It would appear to us that agricultural land has some key characteristics in common with gold. The main ones being;

- It is a finite resource and is valuable, primarily, as a result of scarcity.

- Typically, both have very low yields (zero or less in the case of gold).

The first of these characteristics, combined with an uncertain global economic outlook, has contributed to an increase in the prices paid for agricultural land in Australia. This has been a double-edged sword; the upside is that it has increased the wealth of those who own land; the downside is that, with no corresponding increase in profits, it reduces the returns on capital.

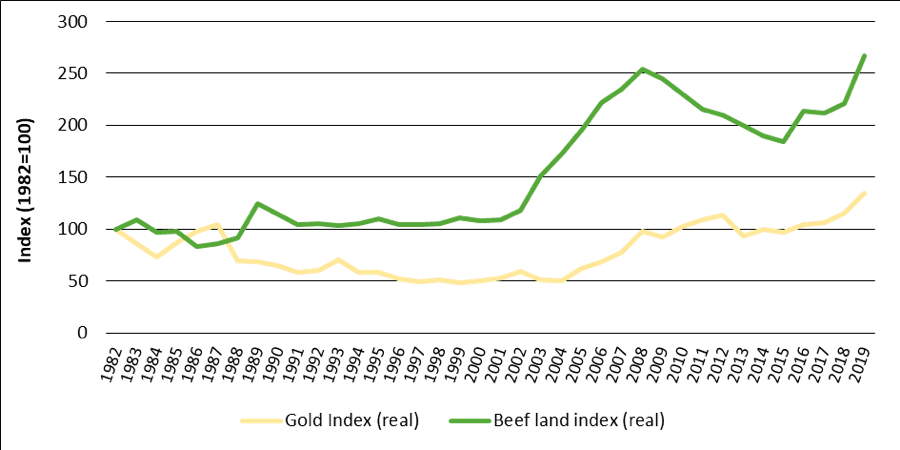

Analysis of historical data indicates that agricultural land in Australia has been a better investment than gold over the last 40 years.

The above graph compares the market price of all beef land in Australia with that of gold. The comparison is in real terms (inflation removed) and both sets of data are indexed to 100 in 1982, the starting year of the analysis. The Beef Land Index is derived from data sourced from ABARES and the Gold Index from data from the World Gold Council.

These data show that over this period, beef land increased in price more than gold. However, it also shows that both assets can go flat for a long time, as happened in the 90’s, and they can decrease in value. If you look at the figure above, nearly all the gains for both effectively happened in one decade, the 2000s.

How to appropriately value rural land?

Rural land being a good store of wealth, and generally increasing in value over time, can cause confusion in how to appropriately value it. Asking ‘what is the purpose of your investment’ is a key question in determining how to value rural land.

Is it:

- a store of wealth?

- a speculative investment in increasing land values?

- an investment that requires an adequate operating return from the capital invested, taking into account risk and opportunity cost?

The approach taken to determining value under each purpose is quite different. For a) and b), the ‘value’ is determined by the market on the day, assuming it is an efficient market and everything is correctly priced. Purpose c) requires an appraisal of the likely returns, the risks involved, and clarity on what return you require on your investment.

At the moment, it is very difficult for those requiring a reasonable return from their investment, to justify purchases at current land prices. There are exceptions, but exceptional yields are generally harder to find at current prices.

This can lead to the argument that, as it is an appreciating asset over time, the returns from capital gains could be factored in to help justify the purchase price. This is what economists refer to as the ‘greater fool theory’, which is where a buyer pays more for an asset than it is intrinsically worth, in the belief that a ‘greater fool’ will come along and pay even more in the future. This approach is b) above, not c).

An advantage of our economy is that individuals and organisations are free to invest and risk their capital on pretty much whatever they want, for whatever reason they want. Investors also have differing risk profiles and investment timeframes. The disadvantage is that buyers from all three approaches above are competing in the same market, with those prepared to pay the most, consequently setting the ‘value’.

This creates a very real problem where a purchaser with purpose c), who does not do his or her due diligence well, and accepts the market price as ‘value’, which has been perhaps set by a purpose a) or b) buyer, is effectively locking in a very low return (see below example). If there is an expectation of good returns, significant debt to service, or both, then the pressure to generate returns can cause the land to be run too hard. This may go on for years and the purchaser may even find a greater fool, who pays even more for the property in spite of any overstocking.

Our opinion is that, for agricultural businesses, approach c) is the most appropriate because;

- the investment provides a return without having to be sold to realise that return (i.e. independent of potential capital gains);

- depending on leverage, the investment can service debt and is not a cash drain on the remaining business, or cash negative if standalone; and,

- the investment has a ‘protective moat’ around it (if there is a decline in the land market or the economy, it is more likely to be able to withstand those variations if it is generating reasonable operating returns).

This is not to say that investment in agricultural land is not a good store of wealth, or that the increase in land value over time should be ignored. There is no question that agricultural land is a good store of wealth. We believe that the returns from capital gains should be secondary to the agricultural operating returns, and be treated as icing on the cake, rather than being necessary to make the investment stack up.

Our approach is not for everyone, and there have been many fortunes made, and lost, through taking the approaches a) and b). In fact, if you look at history, all the great Australian agricultural fortunes, from Macarthur, through Kidman, to the present day, have been made primarily through land dealing rather than profitable activity on the landscapes.

The Australian Beef Report 2020 Vision has been prepared for those producers who want to generate financial returns from their operating business, and rather than being dependent on capital gains.

This article was published by Beef Central on 19/06/20.